Cammer–the real story of the legendary Ford 427 SOHC V8

In the 1960s, Ford’s overhead-cam 427 V8, popularly known as the Cammer, became the stuff of myth and legend. Here’s the story behind the story.

Here in 2014, overhead-cam, multi-valve engines are the industry standard. Anything less is considered retrograde. But on the American automotive scene of the 1960s, pushrod V8s were the state of the art. Into this simpler, more innocent world stepped Ford’s 427 CID SOHC V8, which soon became known as the Cammer. Even today, a powerful mystique surrounds the engine. Let’s dig in for a closer look.

The first public mention of the Cammer V8 appeared in the Daytona Beach Morning Journal on Feb. 23, 1964. Beaten up at Daytona all month by the new 426 Hemi engines from the Dodge/Plymouth camp, Ford officials asked NASCAR to approve an overhead-cam V8 the company had in the works. But as the Journal reports here, NASCAR boss Bill France turned thumbs down on Ford’s proposed engine. France regarded overhead cams and such to be European exotica, a poor fit with his down-home vision for Grand National stock car racing.

Even though France barred the SOHC V8 from NASCAR competition, Ford proceeded to develop the engine anyway, hoping to change Big Bill’s mind. In May of 1964, a ’64 Galaxie hardtop with a Cammer V8 installed was parked behind Gasoline Alley at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, where the assembled press corps could get a good look at it. Here’s Ray Brock, publisher of Hot Rod magazine, eyeballing the setup. Note the spark plug location at the bottom edge of the valve cover on this early version of the SOHC V8.

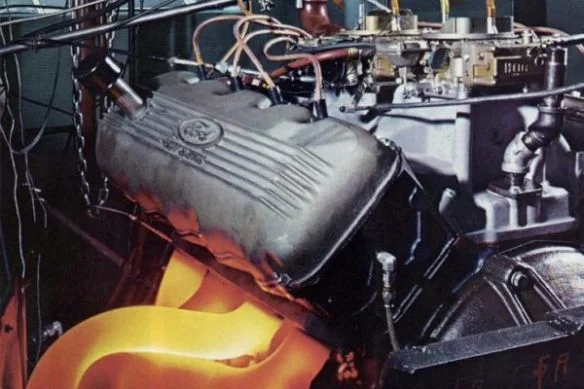

Here’s another early photo of a Cammer with the original spark plug location. Ford engineers took great pains to design a perfectly symmetrical hemispherical combustion chamber with an optimized spark plug location, only to discover that the spark plug didn’t really care. The plugs were then relocated at the top of the chamber for ease of access. This engine is set up for NASCAR use: Note the cowl induction airbox, the single carburetor, and the cast exhaust manifolds.

Despite the Cammer’s exotic cachet, in reality the engine was simply a two-valve, single-overhead-cam conversion of Ford’s existing 427 FE V8, and a quick and cheap one at that. Inside the company, the Cammer was known as the “90 day wonder,” a low-investment parallel project to the expensive DOHC Indy engine based on the Ford small-block V8. To save time and money on the conversion, the heads were cast iron and the cam drive was a roller chain. The oiling system was revised and to manage the greater horizontal inertia loads generated by the increased rpm, cross-bolted main caps were incorporated into the block casting. These features were then adopted on all 427 CID engines across the board.

This is not a SOHC Ford V8 but a 331 CID early Chrysler Hemi, shown here to illustrate a major attraction of the SOHC layout among Ford engineers. By placing the camshafts atop the cylinder heads, the pushrods could be eliminated altogether, permitting larger, straighter intake ports.

One Cammer feature that continues to fascinate gearheads today is the timing chain—it was nearly seven feet long. Cheaper and quicker to develop than a proper gear drive but not nearly as effective, the chain introduced a number of issues. For example, racers in the field soon learned that it was necessary to stagger the cam timing four to eight degrees between banks to compensate for slack in the links

This closeup illustrates the revised spark plug location and another issue created by the chain drive. Since the chain drives both cams in the same direction, on one bank the cam rotates toward the intake follower, and away from the follower on the opposite bank. This in turn necessitated a unique camshaft for each bank, one a mirror of the other, so the opening and closing ramps would be properly located.

Here’s a glamour shot of the complete Cammer from the Society of Automotive Engineers paper (SAE 650497) presented by Norm Faustyn and Joe Eastman, Ford’s two lead engineers on the project. All the published technical sources on the Cammer, including an in-depth feature in the January 1965 issue of Hot Rod Magazine, appear to be closely based on the SAE paper.

On October 19, 1964, NASCAR moved to ban all “special racing engines,” in its words, eliminating both the Cammer Ford and the Chrysler 426 Hemi from Grand National competition for 1965. Chrysler responded by temporarily withdrawing from NASCAR, while Ford continued on with its conventional 427 pushrod engine in NASCAR and took the SOHC engine to the drag strips.

Cammers were first employed in the handful of factory-backed ’65 Mustangs and ’65 Mercury Comets racing in the NHRA Factory Experimental classes and elsewhere. Shown here is the installation in Dyno Don Nicholson’s Comet. Over the ’65 season, Nicholson experimented with Weber carbs and Hilborn fuel injection setups, along with the dual Holley four-barrels pictured. On gasoline, the engine was said to be good for 600 hp.

Despite heavy lobbying from Ford, in December of 1965 NASCAR again banned the Cammer for 1966, with USAC piling on (Spartanburg Herald-Journal, December 18, 1965 above). However, in April of 1966 NASCAR finally relented. Sort of. Okay, not really. The Cammer was now allowed, technically, but only in the full-size Galaxie model, limited to one small four-barrel carb, and with an absurd, crippling weight handicap: nearly 4400 lbs, 430 lbs more than the Dodge and Plymouth hemis. At that point Ford said no thanks and dedicated the Cammer to drag racing. The engine never turned a lap in NASCAR competition.

Ford made the Cammer widely available in the drag world, providing engine deals to nitro racers Tom Hoover, Pete Robinson, Connie Kallita, and a host of others. Here, driver Tom McEwen and engine wizard Ed Pink sort out their Cammer-powered AA/Fuel Dragster at the 1967 U.S. Nationals. Among the most successful Cammer-equipped drag cars were the 1966-67 Comet flip-top funny cars (Don Nicholson, Eddie Schartman, et. al.) and Mickey Thompson’s dominating ’69 Mustang team starring Danny Ongais and Pat Foster.

Drag racers burned midnight oil tackling the Cammer’s issues, including the mile-long timing chain. Working with Harvey Crane of Crane Cams and P&S Machine, the always creative Pete Robinson produced this gear drive system. Note the additional gear on the left bank, allowing a right-hand camshaft to be used on both cylinder heads.

Cammer engines are very scarce these days, and when you can find one, very expensive. Reproduction heads are sometimes available, but they’re pricey, too. It’s difficult to fathom that in the late ’60s and early ’70s, Cammers were OE surplus. Gratiot Auto Supply, the famed Detroit speed shop, sold complete engines new in the crate for $2300. Connie Kalitta was a stalwart Ford Cammer racer back in the day, as shown in this 1967 photo, and he continues to operate a multi-car Top Fuel and Funny Car team in 2014. He’s told MCG that with modern upgrades, the basic Cammer design would make a great Top Fuel engine today.